Luisa Cristini, PhD, University of Hawaii at Manoa

[Note from the editor: This is the sixth in a series of blog entries that will focus on introductory topics in climate dynamics and modeling, and will be a great insight into the current understanding of the science.]

One of Earth’s unique and finite resources is water. Water means life for animals and plants. The development of human society has always followed water resources, since we need it for our fundamental needs and to maintain a high standard of living. However, nowadays water resources are under pressure from both natural and human origin.

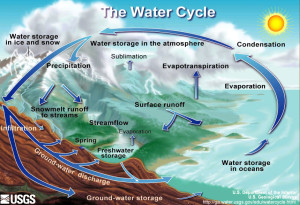

Water on Earth is distributed via the hydrological cycle (or water cycle), composed of rainfall, evaporation, groundwater, and storage. It includes water in all its three physical states: liquid, solid and gas. The water cycle has a considerable impact on the radiative balance: water vapor is the most important greenhouse gas in the atmosphere, the presence of snow and ice strongly modifies the albedo of the surface, and clouds influence both the longwave and shortwave fluxes on Earth. Moreover, water is an essential vehicle for energy: the latent heat released during the condensation of water is a dominant heating source for the atmosphere, and the transport of water vapor in the atmosphere and of water at different temperatures in the ocean are essential in the horizontal heat transport.

The hydrological cycle is also essential in shaping the Earth’s environment, the availability of water being a critical factor for life and for many chemical reactions and transformations affecting the physical environment. The various components of the hydrological cycle and the mechanisms responsible for the exchanges of water between the different reservoirs are thus very important for the whole climate system.

The largest water reservoir on Earth is located in its crust, with volume estimates on the order of 1022 kg of water. This is about 10 times the amount of water in the oceans, the second largest reservoir. Groundwater and soil moisture, which store a significant amount of water, interact quickly with the ocean and the atmosphere.

A large amount of water is also stored in form of ice, mainly on the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets. By contrast, the stock of water in the atmosphere is very low (12,700 km3).

The water precipitated from the atmosphere is replaced through evaporation over the ocean and other water bodies as well as by evaporation and vegetative transpiration over land. Most of the water that evaporates over the ocean falls back over the ocean, and similarly the water that evaporates over land, usually falls back over land. There is also water transfer by the atmosphere from the oceanic area to the land area. This net transfer corresponds to roughly 35% of the total precipitation over land, and is compensated by a surface flow of water (mainly in rivers) from the land to the sea.

Intense evaporation occurs in the warm equatorial areas and in the tropics. In equatorial areas, because of the convergence at the surface and upward motions, the moist air at low levels rises, reaching colder levels. This induces condensation, the formation of clouds and consequently higher precipitation rates.

Throughout Earth’s history the hydrological cycle has been changing naturally. However, in the last couple of centuries ongoing human activities have started to become primary “drivers” of stress and change in the water system. These pressures are generally related to human development and economic growth.

Historically, groundwater resources have been heavily used for agriculture and human supply. Today, almost all industries make use of large amounts of water in the production of goods and services, including energy. Human activities affect both water quality (i.e. contamination) and quantity (i.e. supply). In some areas of the world, pollution of important river basins and aquifers has reached, or exceeded, a point of no return. In these areas a future without secure water resources is fast becoming a reality.

Climatologists now agree that current and future global warming will result in an intensification, acceleration, or enhancement of the hydrological cycle, and observations indicate that this is already happening.

References

Goosse H., P.Y. Barriat, W. Lefebvre, M.F. Loutre and V. Zunz, (2012). Introduction to climate dynamics and climate modeling. Online textbook available at http://www.climate.be/textbook.

IPCC (2007): Fourth Assessment Report: Climate Change 2007. http://ipcc.ch/publications_and_data/publications_and_data_reports.shtml#1

UNESCO (2009): World Water Development Report: Water in a Changing World. http://www.unesco.org/new/en/natural-sciences/environment/water/wwap/wwdr/wwdr3-2009/downloads-wwdr3/

Comments are closed.