By Gavin Roy

After the 2004 Christmastime earthquake and tsunami in the northeastern Indian Ocean that killed over 230,000 people and displaced another 1.8 million, Indonesia took bounding steps toward an effective early tsunami warning system. However, like any system under development, kinks and roadblocks must first be worked out in order to arrive at a properly-functioning solution.

In the wake of the 2004 tsunami, the Indonesian Meteorology, Geophysics, and Climatology Agency (IMGCA) in Jakarta launched a new tsunami warning branch. Staffed round-the-clock by 30 scientists, the branch keeps an eye on the seismographic and oceanographic situation using data from buoys, tidal gauges, and seismographs. The goal is to issue broad-scale tsunami warnings within five minutes of any undersea earthquake that has the potential to generate a large tsunami. Initially, IMGCA set their criteria to a magnitude of 7.0 or higher on the Richter scale with an epicenter depth of 70 kilometers or less.

This warning system was put to the test in October of 2010 when a magnitude 7.7 earthquake struck off the coast of Sumatra, Indonesia’s largest island. It went on to generate a tsunami that, despite successful warnings less than five minutes after the quake, killed over 400 people and displaced over 20,000. IMGCA later stated that the wave came faster than its sensors’ ability to detect the extreme, sudden changes in water levels.

Ground-based GPS sensors could be the answer to the problem. These sensors would be installed at key locations along Sumatra’s fault line (both underwater and on dry land). The instant any sensor moves as little as a millimeter due to tectonic shifting, the motion would be detected by satellites and relayed back to the tsunami warning branch of IMGCA. Calculations would quickly be run to determine if the intensity and breadth of the motion was enough to merit a tsunami warning. Gaining even a minute of warning time could mean the difference between 100 and 1,000 deaths.

Ground-based GPS sensors could be the answer to the problem. These sensors would be installed at key locations along Sumatra’s fault line (both underwater and on dry land). The instant any sensor moves as little as a millimeter due to tectonic shifting, the motion would be detected by satellites and relayed back to the tsunami warning branch of IMGCA. Calculations would quickly be run to determine if the intensity and breadth of the motion was enough to merit a tsunami warning. Gaining even a minute of warning time could mean the difference between 100 and 1,000 deaths.

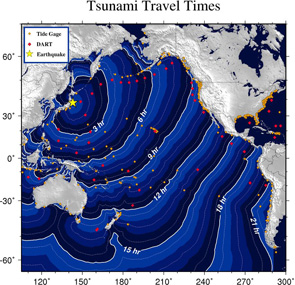

Tsunami Travel Times

Government research officials are hoping to have this technology integrated and operational by 2013. Until then, seismographers at IMGCA will continue to use currently available records of earthquakes to be ready for a worst-case scenario, should it become a reality.

References

Craymer, Lucy, et al. “Tsunami Goes Far But Loses Its Punch” wsj.com. The Wall Street Journal. 12 March 2011. Web. 12 January 2012.

Pathoni, Ahmad. “Indonesian Tsunami Early Warning Words, but Problems Remain.” Monsters and Critics. 26 December 2011. Web. 12 January 2012.

Image Source: http://www.mymorningjoe.com

Comments are closed.